In pursuit of its extreme neoliberal agenda, our Federal Government is steadily dismantling our regulatory systems and destroying public interest science. It needs to stop.

Two recent developments are encouraging signs that regulators in some countries are actually starting to grapple with how to address the rapidly increasing use of nanomaterials in consumer products. Canada has implemented a reporting requirement for products containing nanomaterials – following the US and several EU countries; and the EU has just finalised its rules for assessing novel foods which require all foods that contain nanomaterials to undergo pre-market safety assessment and authorisation.

Meanwhile, Australia is starting to feel more and more like an isolated island at the bottom of the world. The Government’s neoliberal agenda has pervaded resource strapped regulators to such an extent that new regulation is regarded as a unacceptable cost to industry, and any new regulatory initiatives have to be ‘offset’ by reducing the ‘regulatory burden’ elsewhere.

We have no nanomaterial register, the vast majority of nanomaterials remain unregulated, and we have no regulator with any real idea as to the scale of nanomaterial use in Australia – nor the risks associated with these materials.

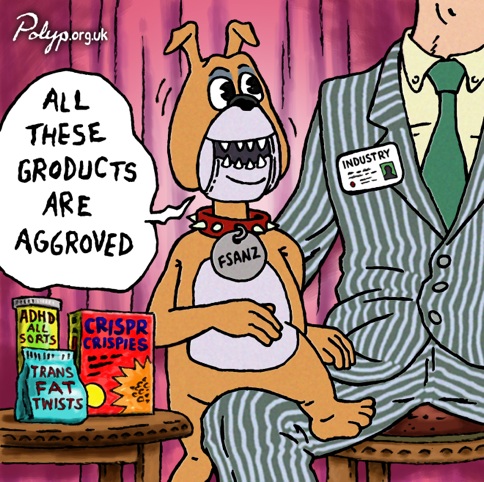

Our food regulator Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) for example, first denied the presence of nanomaterials in food. Then – when proven wrong – claimed the nanomaterials were safe without any testing or analysis. That assertion was based on a lie – that the best predictor of the safety of nanomaterials is whether they are safe at conventional scale. Most reputable scientific bodies disagree. Environment Canada asserts, for example, that these same substances, at nanoscale, “exhibit unique properties which may give rise to new exposures and effects which need to be assessed for their potential risk to human health and the environment.”

Despite a broad consensus that nanomaterials need separate assessment, FSANZ did nothing about the presence of nanomaterials in food. Even the basic step of a register, which would allow regulators to understand exposure pathways and track impacts should they occur, is viewed as too large a burden for industry.

In January this year, the Australian Pesticide and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) released a strategy in which they declared that decisions regarding the safety of chemicals used on foods could be made even if there was inadequate data. This week, the EU Ombudsman found the European Commission guilty of maladministration for taking exactly that approach to chemical approvals. FSANZ too repudiates the precautionary principle meaning the safety of foods, food additives and food chemicals does not have to be firmly established before commercialisation.

The National Industrial Chemical Notification and Assessment Scheme (NICNAS) recently announced implementation of a new assessment model that would see the number of new chemicals subject to regulatory assessment in Australia reduced by 70% in favour of ‘industry self regulation’.

We all know who pays in the end. All of these regulatory backward steps benefit industry and leave the public at greater risk. All of these steps affect the foods we eat and the health of our soil and water. It may take a while before we know what those impacts are because there is no surveillance system in place that would allow that to happen, but there is no question that there will be impacts and no question that industry won’t pay for them.

Since our regulators don’t demand good data to determine the safety or otherwise of chemicals and foods, we rely on public interest science to do that work and the Turnbull Government is busy taking the axe to that as well.

Welcome to our very own corporate state.